Responding to meanness – let people be

“This might not strike you as an intellectual bombshell, but people like to sit where there are places for them to sit.”

I think about that quote from William H. Whyte a lot, ever since I encountered it, handily enough, in the Project for Public Spaces' A Primer on Seating. I think about it as I travel, as I wander through new cities and old, as I look at my own neighborhoods and regular haunts. Where are people sitting – if there are people around to sit? Where are people invited or disinvited to sit? Where can people be?

That's the clash at the heart of the new City Pages article, A Town Turned Mean, about a change in feeling on Hennepin Avenue. The overall tone of the article is one of worry, of anxiety, people feeling like something is slipping away. What happens in a city when no-one feels welcome?

Part of it comes down to the physical space of Hennepin Avenue. I was walking down Sixth Street in Austin, TX, last weekend, which has more bars and venues than you can count on each block. There were more people, more substances consumed, more opportunities for meanness, but it was really pleasant and convivial, because they had blocked off the street for pedestrians, and people had space to be. We concentrate people on the sidewalks on Hennepin, and expect it to be a nightlife hub and major thoroughfare, and that's just a mess of expectations. The main article has people noting that quality of life issues like public urination seem to be on the rise, but a reader then writes in that there are no public restrooms on Hennepin. We haven't made it a place to be.

The failing is not for lack of trying. Joan Vorderbruggen, quoted in the City Pages piece, has been putting together the MadeHere window installations and the 5 to 10 on Hennepin art parties, but single arts interventions do not change the culture or a built environment. With a major redesign of Hennepin on the horizon, pushing city council members and mayoral candidates on where the places to sit will be and who gets to sit there is crucial for the future.

It's also something that has to be prioritized as cities compete on identity and amenities. Outgoing director of design and creative placemaking at the National Endowment for the Arts Jason Schupbach put it succinctly in his exit interview. "I have a bee in my bonnet about why more community development and planning students don’t learn any cultural policy," Jason says. "If you ever ride on an airplane and look at the airplane magazine, there’s always a special section where a city is marketing itself and half of the items are about cultural things. If this is the primary way cities market themselves, why don’t more of the people doing community development understand the policies that shape these culturally unique places?"

Those policies are ones that create places to sit, create belonging or disbelonging. What the City Pages article leaves out is that there is a large race and class divide between the visitors coming into downtown and the people sitting, loitering, being on the avenue. Visitors tend to be white, people being there tend to be black. I don't have numbers, but I go downtown, and I have eyes, which seems to be the City Pages' standard for this article. Many commenters on the story also point out this omission, often gleefully with commentary along the lines of "What PC nonsense in a liberal city." Many of those commenters also seem to come suburbs, which, due to re-investment in cities and the urban core and shifting housing affordability, are becoming more diverse. So their time will come. We need to do better in the city, so that suburbs have better models and don't repeat our mistakes.

But that omission is important, that divide is important, that discomfort is important, because we're not comfortable discussing that discomfort, and while we are talking about institutional racism, we have yet to dismantle it, untangle it from use of public space. I was in San Francisco on June 16th, the afternoon of the Philando Castile verdict, where the police officer who shot 7 rounds into a car 74 seconds after meeting a man was acquitted of any crimes. I was sitting in the ballroom of the Hilton downtown at the Americans for the Arts Convention, and the keynote speaker, who started just as the verdict rolled in, was Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative.

Stevenson is a profound and powerful speaker. The work that EJI is doing around mass incarceration, and confronting the history of lynching in America is deep, discomfiting, critical work. Stevenson's talk hinged on the power of art in everyday life to connect people, to empower them, to give them a chance to be heard, and he had four major points on how we enact change. We have to get proximate to the poor, he said, we have to change narratives of who is seen as criminal, as having power, as being important in society. We have stay hopeful, and we have to do uncomfortable and inconvenient things.

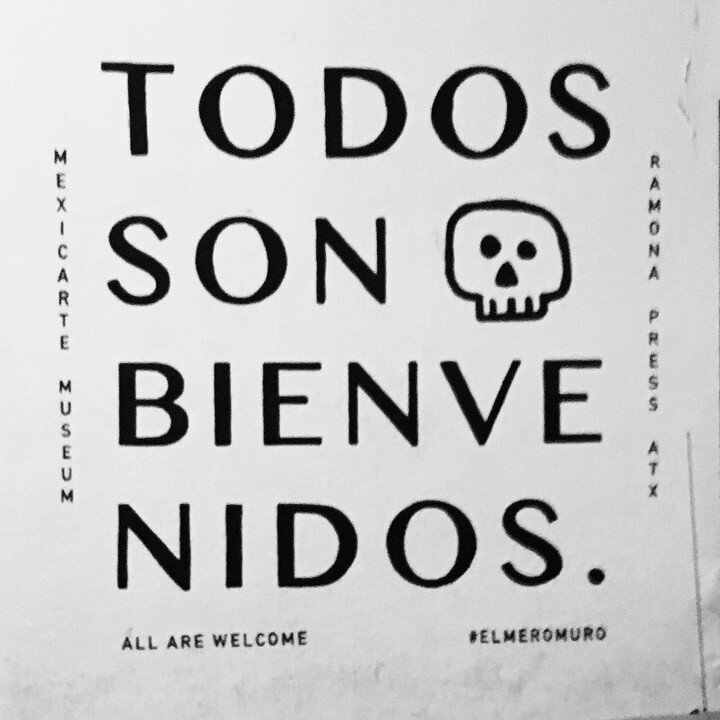

I – and I was not alone – was weeping in that hotel ballroom by the end of Stevenson's talk. Hennepin Avenue is failing us on all those counts right now – because we're not figuring out how to be in the same space together in an effective and ongoing way. I was at a 5 to 10 on Hennepin event before Pride, where Kulture Klub artists were performing on stage, queer youth of color were dancing, old black dudes were playing chess with young white professionals (that photo is right there in the City Pages article) and I got to compare our kids' facepaint with young black moms. We can do this, we can invest space, in education, in places for people to sit together, to be together.

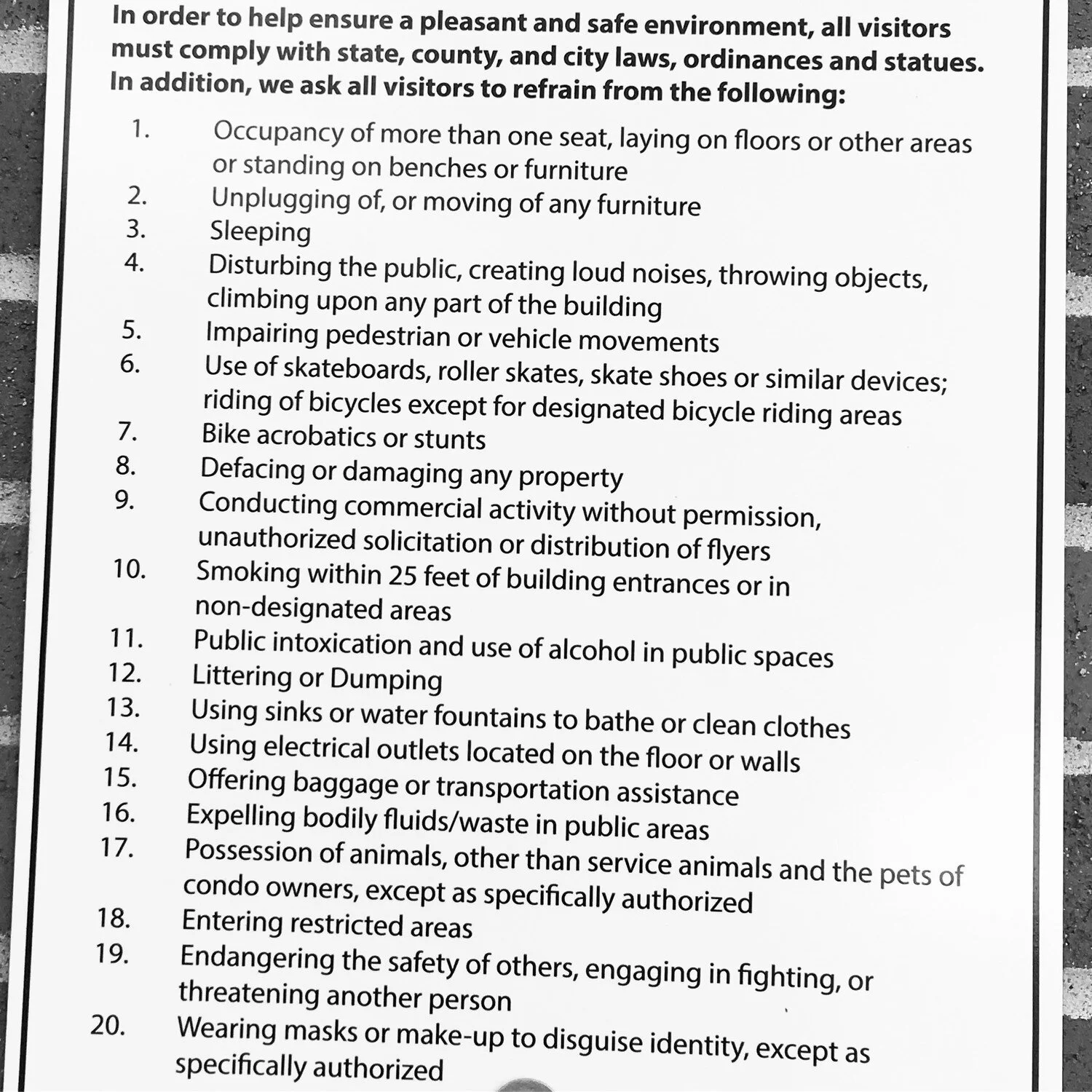

It's not just in the one downtown. Across the river, at the Union Depot, there was a buzz of activity outside for the recent all-night Northern Spark festival. Projections on the building, art projects and installations outside, people wandering in and out of the building. Outside was hopping, inside there were signs that told visitors that seating was only for ticketed passengers. Poor rent-a-cops were telling people resting their feet in front of Ta-Coumba Aiken's lite-brite mural that they had to move along, unless they had a train ticket. Who were they kidding? Union Depot has a whole list of rules – rules that I'm sure well-meaning people concerned about safety would want to default to – that make up what falls into the "arsenal of exclusion," discrimination in list form.

In the bigger picture, this is about a feeling being comfortable with other people. We have such deep racial, class and social inequities in these cities and in this state. We segregate in the name of social order and comfort. Some of that is structural by regulation and policy, some of that is structural by cultural norms. In a community with at least 5 shootings or killings of young black men in the last 4 years (Terrence Franklin, Jamar Clark, Philando Castile, Cordale Handy, Khaleel Thompson) the trauma is running deep, and we need to face that and find ways to be together, before anything gets better on a single street. I don't know how to tell you to listen to others, and believe them, other than to do it, and to let them be in their own way.

My friend Lindsay is on a trip to Germany and shared an experience at Nueschwanstein Castle, the fairytale image of a palace. On the bridge to take pictures of the castle, a woman had taken it upon herself to enforce what she saw as appropriate line behavior, telling people where to go and how to stand. Lindsay tweeted out a thread about how this affected her, in the context of her visit to Germany. "We don't need to police each other's behavior in social settings," she sent. "What you do, if you're not harming others, is none of my business. This lady clearly felt it was her responsibility to make sure no one broke the unspoken rules, and maybe it's because I spent the previous days at Nazi museums and Dachau, but self-appointed policing of others is on the continuum of oppressive authoritarianism oppressive regimes work better when citizens regulate and police each other, and we need less of that in this world."

I'm lucky enough to travel and be in other cities. When I was in San Francisco, looking to save a little money on the conference hotel, I booked a room in a single occupancy hotel in the Tenderloin – a gussied up flophouse with a shared bathroom. And in the Tenderloin, there are all sorts of people, and a lot of behaviors that a city wouldn't want on it's main commercial thoroughfares or nightlife hubs. I got offered a lot of drugs, saw a lot of IV drug users, but weirdly enough, didn't feel particularly unsafe, because there were always people around, and people all had, or brought, or made places to sit. Users, business owners, families, they were all there. Part of the neighborhood advertising read "Tenderloin: Where we tend to know our neighbors." That was comforting, even for a stranger interloping into the community for a minute. Having people feeling like they are part of a place makes a place safer.

"New York I love you, but you're bringing me down," James Murphy sings in LCD Soundsystem's 2007 track of the same name, cutting into what Murphy sees as the neutering and sterilization of his gritty city. Surely Times Square's transformation from major thoroughfare to pedestrian hub would chagrin the singer, but that change made the space safer, made it more welcoming, gave people a place to sit. We have to make those big changes, do things in a new way, invest in the people that live and work in a space, whether they are business owners, tourists, or people experiencing homelessness. A city is the collection of the people who pass through it, and their interactions make up the identity of a place. Let's start facing down structural racism by re-imagining how our thoroughfares are used. Let's let people sit, let people pee, let people be.